Челести, Андреа. Андреа челести картины

Челести, Андреа — Википедия (с комментариями)

Материал из Википедии — свободной энциклопедии

Андре́а Челе́сти ( итал. Andrea Celesti ; 1637, Венеция — 1712, Тосколано ) — итальянский художник венецианской школы второй половины XVII — начала XVIII века. Наследник венецианских колористов, он разрабатывал традиционную для эпохи барокко канву религиозно-мифологических сюжетов. Позднее его приёмы стремительно-воздушной лёгкости красочной кладки[1] очень пригодились живописцам рококо[2].

Биография

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

Напишите отзыв о статье "Челести, Андреа"

Литература

- Государственный музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина. Каталог живописи / Под общ. ред.: И. Е. Даниловой; Пер. на англ. яз.: Э. Бромфилд. — Москва, Милан: ART-MIF, Mazzotta, 1995. — С. 210—211. — 775 с.

- [books.google.ru/books?id=WsqmcBdytuEC История живописи всех времен и народов]. — СПб, Москва: Издательский Дом “Нева”, ОЛМА—ПРЕСС, 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с. — ISBN 5765421105.

- Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи : Италия. Испания. Франция. Швейцария / Вступ. статья В. Ф. Левинсон-Лессинга. — Москва, Ленинград: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.

- Andrea Celesti a Desenzano : capolavori nella chiesa di S. Maria Maddalena. — Acherdo Edizioni, 2009. — 69 p. — ISBN 8890415304.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : la Strage degli innocenti restaurata. — Brescia: Grafo, 2007. — 69 p. — ISBN 8873857426.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : capolavori restaurati nella Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo. — Brescia, Italy: Grafo, 2006. — 100 p.

- Isabella Marelli; Giuliana Algeri. Andrea Celesti (1637-1712) : un pittore sul Lago di Garda. — Brescia: San Felice del Benaco, 2000. — 369 p. — 2000 экз.

- Giovanni Agosti; Elena Lucchesi Ragni. Andrea Celesti nel Bresciano : per il restauro del ciclo di Toscolano (1678—1712). Exhibition catalog. — Brescia, Italy: Civici Musei d'arte e storia, 1993. — 47 p.

- Camillo Boselli [www.cbt.biblioteche.provincia.tn.it/oseegenius/resource?uri=2070050 Appunti bresciani ad un libro su Andrea Celesti] (Italiano) // Arte veneta / Istituto di Storia dell'Arte. — Venezia. — Università di Padova, 1955. — № 33—36. — С. 234—236.

- Antonio Morassi. Il pittore Andrea Celesti. — Milano: Silvana, 1954. — P. 168.

Галерея

-

Andrea Celesti Virgen de las Uvas.jpg

-

Andrea celesti painting1.jpg

-

Andrea Celesti - King David Playing the Zither - WGA04619.jpg

-

Andrea Celesti Festín de Baltasar 1705 Hermitage.jpg

-

Andrea Celesti - The Virgin and Child with the Infant St John Appearing to St Jerome and St Anthony - WGA04623.jpg

-

Andrea Celesti (attr) Tod des Königs Priamos.jpg

-

Tamerlan und Bajazet (Celesti).jpg

Ссылки

- [www.wga.hu/html_m/c/celesti/index.html 6 работ Андреа Челести, включая монументальные]

- [www.youtube.com/watch?v=0k9cJA3fnxQ Моника Мольтени (Monica Molteni)], профессор Университета Вероны (англ.), о современных исследованиях живописи Андреа Челести и проблемах реставрации (ВИДЕО, 4 мин.) (итал.)

- Интересно проследить за методом создания композиции на примере [www.artnet.com/artists/andrea-celesti/past-auction-results рисунка, исполненного тушью, «Похищение Европы» (20 x 26.7 см)], атрибутируемого Андреа Челести.

- Сравним с [www.artnet.com/artists/andrea-celesti/compianto-sul-cristo-morto-5pSvJ8pk4frQAZqtTavb9w2 небольшим эскизом Андреа Челести «Сцена оплакивания мёртвого Христа» (перо, тушь 14 x 9.8 см).]

- Ещё один рисунок, приписываемый А. Челести из музея Метрополитен в Нью-Йорке: [www.metmuseum.org/collection/the-collection-online/search/338445 эскиз для заказной картины «Аллегория власти Венеции»] (отмывка коричневой тушью, перо, сангина, 37.0 x 28.5 см), основательно прорисованная аллегорическая многофигурная композиция[6].

Примечания

- ↑ Русский художник и историк искусства Александр Бенуа называет живописную манеру Андреа Челести «красивой и сочной». См: История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, М., 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с.

- ↑ По словам крупного знатока итальянской живописи, Макса Геринга,

за двадцать лет до рождения Гварди, Андреа Челести достиг импрессионистского растворения формы

— (См: Max Goering. Francesco Guardi. — First Edition. — Wien: Anton Schroll & Co., 1944. — P. 30. — 86 p. — ISBN 0011251239.)

- ↑ Андреа Челести 1637—1706. Венецианская школа. Учился у Маттео Панцоне, испытал влияние венецианских художников XVI в. Работал в Венеции. Писал картины на религиозные и мифологические темы и портреты. (В книге: Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи. — М., Л.: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.)

- ↑ Ivanoff N. Celesti, Andrea // [www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/andrea-celesti_(Dizionario-Biografico)/ Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani]. — Rome: Institutto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

- ↑ Программа фестиваля «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести» Borghese, Fabio. [www.vallesabbianews.it/notizie-it/Andrea-Celesti-il-teatro-del-colore-27421.html Andrea Celesti, il teatro del colore]. «Treccani» La cultura italiana (20 февраля 2014). Проверено 22 января 2016. (итал.)

- ↑ Рисунок «Аллегория власти Венеции» опубликован в капитальном томе: Jacob Bean, Lawrence Turčić. [archive.org/details/SeventeenthCenturyItalianDrawingsinTheMetropolitanMuseumofArt 17th century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art]. — New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979. — P. 94—95.

Отрывок, характеризующий Челести, Андреа

– Граф страдает и физически и нравственно, и, кажется, вы позаботились о том, чтобы причинить ему побольше нравственных страданий. – Могу я видеть графа? – повторил Пьер. – Гм!.. Ежели вы хотите убить его, совсем убить, то можете видеть. Ольга, поди посмотри, готов ли бульон для дяденьки, скоро время, – прибавила она, показывая этим Пьеру, что они заняты и заняты успокоиваньем его отца, тогда как он, очевидно, занят только расстроиванием. Ольга вышла. Пьер постоял, посмотрел на сестер и, поклонившись, сказал: – Так я пойду к себе. Когда можно будет, вы мне скажите. Он вышел, и звонкий, но негромкий смех сестры с родинкой послышался за ним. На другой день приехал князь Василий и поместился в доме графа. Он призвал к себе Пьера и сказал ему: – Mon cher, si vous vous conduisez ici, comme a Petersbourg, vous finirez tres mal; c'est tout ce que je vous dis. [Мой милый, если вы будете вести себя здесь, как в Петербурге, вы кончите очень дурно; больше мне нечего вам сказать.] Граф очень, очень болен: тебе совсем не надо его видеть. С тех пор Пьера не тревожили, и он целый день проводил один наверху, в своей комнате. В то время как Борис вошел к нему, Пьер ходил по своей комнате, изредка останавливаясь в углах, делая угрожающие жесты к стене, как будто пронзая невидимого врага шпагой, и строго взглядывая сверх очков и затем вновь начиная свою прогулку, проговаривая неясные слова, пожимая плечами и разводя руками. – L'Angleterre a vecu, [Англии конец,] – проговорил он, нахмуриваясь и указывая на кого то пальцем. – M. Pitt comme traitre a la nation et au droit des gens est condamiene a… [Питт, как изменник нации и народному праву, приговаривается к…] – Он не успел договорить приговора Питту, воображая себя в эту минуту самим Наполеоном и вместе с своим героем уже совершив опасный переезд через Па де Кале и завоевав Лондон, – как увидал входившего к нему молодого, стройного и красивого офицера. Он остановился. Пьер оставил Бориса четырнадцатилетним мальчиком и решительно не помнил его; но, несмотря на то, с свойственною ему быстрою и радушною манерой взял его за руку и дружелюбно улыбнулся. – Вы меня помните? – спокойно, с приятной улыбкой сказал Борис. – Я с матушкой приехал к графу, но он, кажется, не совсем здоров. – Да, кажется, нездоров. Его всё тревожат, – отвечал Пьер, стараясь вспомнить, кто этот молодой человек. Борис чувствовал, что Пьер не узнает его, но не считал нужным называть себя и, не испытывая ни малейшего смущения, смотрел ему прямо в глаза. – Граф Ростов просил вас нынче приехать к нему обедать, – сказал он после довольно долгого и неловкого для Пьера молчания. – А! Граф Ростов! – радостно заговорил Пьер. – Так вы его сын, Илья. Я, можете себе представить, в первую минуту не узнал вас. Помните, как мы на Воробьевы горы ездили c m me Jacquot… [мадам Жако…] давно. – Вы ошибаетесь, – неторопливо, с смелою и несколько насмешливою улыбкой проговорил Борис. – Я Борис, сын княгини Анны Михайловны Друбецкой. Ростова отца зовут Ильей, а сына – Николаем. И я m me Jacquot никакой не знал. Пьер замахал руками и головой, как будто комары или пчелы напали на него. – Ах, ну что это! я всё спутал. В Москве столько родных! Вы Борис…да. Ну вот мы с вами и договорились. Ну, что вы думаете о булонской экспедиции? Ведь англичанам плохо придется, ежели только Наполеон переправится через канал? Я думаю, что экспедиция очень возможна. Вилльнев бы не оплошал! Борис ничего не знал о булонской экспедиции, он не читал газет и о Вилльневе в первый раз слышал. – Мы здесь в Москве больше заняты обедами и сплетнями, чем политикой, – сказал он своим спокойным, насмешливым тоном. – Я ничего про это не знаю и не думаю. Москва занята сплетнями больше всего, – продолжал он. – Теперь говорят про вас и про графа. Пьер улыбнулся своей доброю улыбкой, как будто боясь за своего собеседника, как бы он не сказал чего нибудь такого, в чем стал бы раскаиваться. Но Борис говорил отчетливо, ясно и сухо, прямо глядя в глаза Пьеру. – Москве больше делать нечего, как сплетничать, – продолжал он. – Все заняты тем, кому оставит граф свое состояние, хотя, может быть, он переживет всех нас, чего я от души желаю… – Да, это всё очень тяжело, – подхватил Пьер, – очень тяжело. – Пьер всё боялся, что этот офицер нечаянно вдастся в неловкий для самого себя разговор. – А вам должно казаться, – говорил Борис, слегка краснея, но не изменяя голоса и позы, – вам должно казаться, что все заняты только тем, чтобы получить что нибудь от богача. «Так и есть», подумал Пьер. – А я именно хочу сказать вам, чтоб избежать недоразумений, что вы очень ошибетесь, ежели причтете меня и мою мать к числу этих людей. Мы очень бедны, но я, по крайней мере, за себя говорю: именно потому, что отец ваш богат, я не считаю себя его родственником, и ни я, ни мать никогда ничего не будем просить и не примем от него. Пьер долго не мог понять, но когда понял, вскочил с дивана, ухватил Бориса за руку снизу с свойственною ему быстротой и неловкостью и, раскрасневшись гораздо более, чем Борис, начал говорить с смешанным чувством стыда и досады. – Вот это странно! Я разве… да и кто ж мог думать… Я очень знаю… Но Борис опять перебил его: – Я рад, что высказал всё. Может быть, вам неприятно, вы меня извините, – сказал он, успокоивая Пьера, вместо того чтоб быть успокоиваемым им, – но я надеюсь, что не оскорбил вас. Я имею правило говорить всё прямо… Как же мне передать? Вы приедете обедать к Ростовым? И Борис, видимо свалив с себя тяжелую обязанность, сам выйдя из неловкого положения и поставив в него другого, сделался опять совершенно приятен. – Нет, послушайте, – сказал Пьер, успокоиваясь. – Вы удивительный человек. То, что вы сейчас сказали, очень хорошо, очень хорошо. Разумеется, вы меня не знаете. Мы так давно не видались…детьми еще… Вы можете предполагать во мне… Я вас понимаю, очень понимаю. Я бы этого не сделал, у меня недостало бы духу, но это прекрасно. Я очень рад, что познакомился с вами. Странно, – прибавил он, помолчав и улыбаясь, – что вы во мне предполагали! – Он засмеялся. – Ну, да что ж? Мы познакомимся с вами лучше. Пожалуйста. – Он пожал руку Борису. – Вы знаете ли, я ни разу не был у графа. Он меня не звал… Мне его жалко, как человека… Но что же делать? – И вы думаете, что Наполеон успеет переправить армию? – спросил Борис, улыбаясь. Пьер понял, что Борис хотел переменить разговор, и, соглашаясь с ним, начал излагать выгоды и невыгоды булонского предприятия. Лакей пришел вызвать Бориса к княгине. Княгиня уезжала. Пьер обещался приехать обедать затем, чтобы ближе сойтись с Борисом, крепко жал его руку, ласково глядя ему в глаза через очки… По уходе его Пьер долго еще ходил по комнате, уже не пронзая невидимого врага шпагой, а улыбаясь при воспоминании об этом милом, умном и твердом молодом человеке. Как это бывает в первой молодости и особенно в одиноком положении, он почувствовал беспричинную нежность к этому молодому человеку и обещал себе непременно подружиться с ним. Князь Василий провожал княгиню. Княгиня держала платок у глаз, и лицо ее было в слезах. – Это ужасно! ужасно! – говорила она, – но чего бы мне ни стоило, я исполню свой долг. Я приеду ночевать. Его нельзя так оставить. Каждая минута дорога. Я не понимаю, чего мешкают княжны. Может, Бог поможет мне найти средство его приготовить!… Adieu, mon prince, que le bon Dieu vous soutienne… [Прощайте, князь, да поддержит вас Бог.] – Adieu, ma bonne, [Прощайте, моя милая,] – отвечал князь Василий, повертываясь от нее. – Ах, он в ужасном положении, – сказала мать сыну, когда они опять садились в карету. – Он почти никого не узнает. – Я не понимаю, маменька, какие его отношения к Пьеру? – спросил сын. – Всё скажет завещание, мой друг; от него и наша судьба зависит… – Но почему вы думаете, что он оставит что нибудь нам? – Ах, мой друг! Он так богат, а мы так бедны! – Ну, это еще недостаточная причина, маменька. – Ах, Боже мой! Боже мой! Как он плох! – восклицала мать.Когда Анна Михайловна уехала с сыном к графу Кириллу Владимировичу Безухому, графиня Ростова долго сидела одна, прикладывая платок к глазам. Наконец, она позвонила. – Что вы, милая, – сказала она сердито девушке, которая заставила себя ждать несколько минут. – Не хотите служить, что ли? Так я вам найду место. Графиня была расстроена горем и унизительною бедностью своей подруги и поэтому была не в духе, что выражалось у нее всегда наименованием горничной «милая» и «вы». – Виновата с, – сказала горничная. – Попросите ко мне графа. Граф, переваливаясь, подошел к жене с несколько виноватым видом, как и всегда. – Ну, графинюшка! Какое saute au madere [сотэ на мадере] из рябчиков будет, ma chere! Я попробовал; не даром я за Тараску тысячу рублей дал. Стоит! Он сел подле жены, облокотив молодецки руки на колена и взъерошивая седые волосы. – Что прикажете, графинюшка? – Вот что, мой друг, – что это у тебя запачкано здесь? – сказала она, указывая на жилет. – Это сотэ, верно, – прибавила она улыбаясь. – Вот что, граф: мне денег нужно.

wiki-org.ru

Челести, Андреа Википедия

Андре́а Челе́сти (итал. Andrea Celesti ; 1637, Венеция — 1712, Тосколано) — итальянский художник венецианской школы второй половины XVII — начала XVIII века. Наследник венецианских колористов, он разрабатывал традиционную для эпохи барокко канву религиозно-мифологических сюжетов. Позднее его приёмы стремительно-воздушной лёгкости красочной кладки[1] очень пригодились живописцам рококо[2].

Биография

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

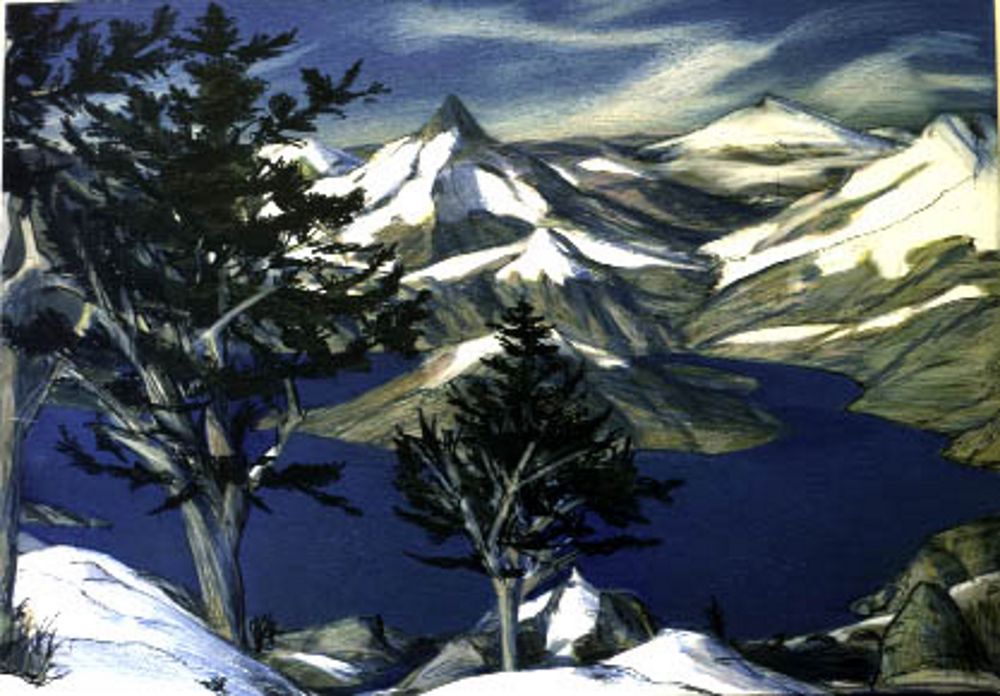

Мадонна с младенцем и святой Анной иблагословляющим святым Иаковом. Холст, масло.Епархиальный музей (Брешия) / Museo diocesano (Brescia)Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:

Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]

Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

Литература

- Государственный музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина. Каталог живописи / Под общ. ред.: И. Е. Даниловой; Пер. на англ. яз.: Э. Бромфилд. — Москва, Милан: ART-MIF, Mazzotta, 1995. — С. 210—211. — 775 с.

- История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, Москва: Издательский Дом “Нева”, ОЛМА—ПРЕСС, 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с. — ISBN 5765421105.

- Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи : Италия. Испания. Франция. Швейцария / Вступ. статья В. Ф. Левинсон-Лессинга. — Москва, Ленинград: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.

- Andrea Celesti a Desenzano : capolavori nella chiesa di S. Maria Maddalena. — Acherdo Edizioni, 2009. — 69 p. — ISBN 8890415304.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : la Strage degli innocenti restaurata. — Brescia: Grafo, 2007. — 69 p. — ISBN 8873857426.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : capolavori restaurati nella Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo. — Brescia, Italy: Grafo, 2006. — 100 p.

- Isabella Marelli; Giuliana Algeri. Andrea Celesti (1637-1712) : un pittore sul Lago di Garda. — Brescia: San Felice del Benaco, 2000. — 369 p. — 2000 экз.

- Giovanni Agosti; Elena Lucchesi Ragni. Andrea Celesti nel Bresciano : per il restauro del ciclo di Toscolano (1678—1712). Exhibition catalog. — Brescia, Italy: Civici Musei d'arte e storia, 1993. — 47 p.

- Camillo Boselli Appunti bresciani ad un libro su Andrea Celesti (Italiano) // Arte veneta / Istituto di Storia dell'Arte. — Venezia. — Università di Padova, 1955. — № 33—36. — С. 234—236.

- Antonio Morassi. Il pittore Andrea Celesti. — Milano: Silvana, 1954. — P. 168.

Галерея

Ссылки

- 6 работ Андреа Челести, включая монументальные

- Моника Мольтени (Monica Molteni), профессор Университета Вероны (англ.), о современных исследованиях живописи Андреа Челести и проблемах реставрации (ВИДЕО, 4 мин.) (итал.)

- Интересно проследить за методом создания композиции на примере рисунка, исполненного тушью, «Похищение Европы» (20 x 26.7 см), атрибутируемого Андреа Челести.

- Сравним с небольшим эскизом Андреа Челести «Сцена оплакивания мёртвого Христа» (перо, тушь 14 x 9.8 см).

- Ещё один рисунок, приписываемый А. Челести из музея Метрополитен в Нью-Йорке: эскиз для заказной картины «Аллегория власти Венеции» (отмывка коричневой тушью, перо, сангина, 37.0 x 28.5 см), основательно прорисованная аллегорическая многофигурная композиция[6].

Примечания

- ↑ Русский художник и историк искусства Александр Бенуа называет живописную манеру Андреа Челести «красивой и сочной». См: История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, М., 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с.

- ↑ По словам крупного знатока итальянской живописи, Макса Геринга,

за двадцать лет до рождения Гварди, Андреа Челести достиг импрессионистского растворения формы

— (См: Max Goering. Francesco Guardi. — First Edition. — Wien: Anton Schroll & Co., 1944. — P. 30. — 86 p. — ISBN 0011251239.) - ↑ Андреа Челести 1637—1706. Венецианская школа. Учился у Маттео Панцоне, испытал влияние венецианских художников XVI в. Работал в Венеции. Писал картины на религиозные и мифологические темы и портреты. (В книге: Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи. — М., Л.: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.)

- ↑ Ivanoff N. Celesti, Andrea // Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. — Rome: Institutto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

- ↑ Программа фестиваля «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести» Borghese, Fabio. Andrea Celesti, il teatro del colore. «Treccani» La cultura italiana (20 февраля 2014). Проверено 22 января 2016. (итал.)

- ↑ Рисунок «Аллегория власти Венеции» опубликован в капитальном томе: Jacob Bean, Lawrence Turčić. 17th century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. — New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979. — P. 94—95.

wikiredia.ru

Челести, Андреа — WiKi

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

Мадонна с младенцем и святой Анной иблагословляющим святым Иаковом. Холст, масло.Епархиальный музей (Брешия) / Museo diocesano (Brescia)Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:

Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]

Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

ru-wiki.org

Челести, Андреа - WikiVisually

1. Венеция – Venice is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto region. It is situated across a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and these are located in the shallow Venetian Lagoon, an enclosed bay that lies between the mouths of the Po and the Piave Rivers. Parts of Venice are renowned for the beauty of their settings, their architecture, the lagoon and a part of the city are listed as a World Heritage Site. In 2014,264,579 people resided in Comune di Venezia, together with Padua and Treviso, the city is included in the Padua-Treviso-Venice Metropolitan Area, with a total population of 2.6 million. PATREVE is a metropolitan area without any degree of autonomy. The name is derived from the ancient Veneti people who inhabited the region by the 10th century BC, the city was historically the capital of the Republic of Venice. Venice has been known as the La Dominante, Serenissima, Queen of the Adriatic, City of Water, City of Masks, City of Bridges, The Floating City, and City of Canals. The City State of Venice is considered to have been the first real international financial center which gradually emerged from the 9th century to its peak in the 14th century and this made Venice a wealthy city throughout most of its history. It is also known for its several important artistic movements, especially the Renaissance period, Venice has played an important role in the history of symphonic and operatic music, and it is the birthplace of Antonio Vivaldi. Venice has been ranked the most beautiful city in the world as of 2016, the name Venetia, however, derives from the Roman name for the people known as the Veneti, and called by the Greeks Eneti. The meaning of the word is uncertain, although there are other Indo-European tribes with similar-sounding names, such as the Celtic Veneti, Baltic Veneti, and the Slavic Wends. Linguists suggest that the name is based on an Indo-European root *wen, so that *wenetoi would mean beloved, lovable, a connection with the Latin word venetus, meaning the color sea-blue, is also possible. The alternative obsolete form is Vinegia, some late Roman sources reveal the existence of fishermen on the islands in the original marshy lagoons. They were referred to as incolae lacunae, the traditional founding is identified with the dedication of the first church, that of San Giacomo on the islet of Rialto — said to have taken place at the stroke of noon on 25 March 421. Beginning as early as AD166 to 168, the Quadi and Marcomanni destroyed the center in the area. The Roman defences were again overthrown in the early 5th century by the Visigoths and, some 50 years later, New ports were built, including those at Malamocco and Torcello in the Venetian lagoon. The tribuni maiores, the earliest central standing governing committee of the islands in the Lagoon, the traditional first doge of Venice, Paolo Lucio Anafesto, was actually Exarch Paul, and his successor, Marcello Tegalliano, was Pauls magister militum. In 726 the soldiers and citizens of the Exarchate rose in a rebellion over the controversy at the urging of Pope Gregory II

2. Болонья – Bologna is the largest city of the Emilia-Romagna Region in Northern Italy. It is the seventh most populous city in Italy, located in the heart of an area of about one million. The first settlements back to at least 1000 BC. The city has been a centre, first under the Etruscans. Home to the oldest university in the world, University of Bologna, founded in 1088, Bologna is also an important transportation crossroad for the roads and trains of Northern Italy, where many important mechanical, electronic and nutritional industries have their headquarters. According to the most recent data gathered by the European Regional Economic Growth Index of 2009, Bologna is the first Italian city, Bologna is home to numerous prestigious cultural, economic and political institutions as well as one of the most impressive trade fair districts in Europe. In 2000 it was declared European capital of culture and in 2006, the city of Bologna was selected to participate in the Universal Exposition of Shanghai 2010 together with 45 other cities from around the world. Bologna is also one of the wealthiest cities in Italy, often ranking as one of the top cities in terms of quality of life in the country, after a long decline, Bologna was reborn in the 5th century under Bishop Petronius. According to legend, St. Petronius built the church of S. Stefano. After the fall of Rome, Bologna was a stronghold of the Exarchate of Ravenna in the Po plain. In 728, the city was captured by the Lombard king Liutprand, the Germanic conquerors formed a district called addizione longobarda near the complex of S. Stefano. Charlemagne stayed in this district in 786, traditionally said to be founded in 1088, the University of Bologna is widely considered to be the first university. The university originated as a centre of study of medieval Roman law under major glossators. It numbered Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarca among its students, the medical school is especially famous. In the 12th century, the families engaged in continual internecine fighting. Troops of Pope Julius II besieged Bologna and sacked the artistic treasures of his palace, in 1530, in front of Saint Petronio Church, Charles V was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII. Then a plague at the end of the 16th century reduced the population from 72,000 to 59,000, the population later recovered to a stable 60, 000–65,000. However, there was also great progress during this era, in 1564, the Piazza del Nettuno and the Palazzo dei Banchi were built, along with the Archiginnasio, the centre of the University

3. Барокко – The style began around 1600 in Rome and Italy, and spread to most of Europe. The aristocracy viewed the dramatic style of Baroque art and architecture as a means of impressing visitors by projecting triumph, power, Baroque palaces are built around an entrance of courts, grand staircases, and reception rooms of sequentially increasing opulence. However, baroque has a resonance and application that extend beyond a reduction to either a style or period. It is also yields the Italian barocco and modern Spanish barroco, German Barock, Dutch Barok, others derive it from the mnemonic term Baroco, a supposedly laboured form of syllogism in logical Scholastica. The Latin root can be found in bis-roca, in informal usage, the word baroque can simply mean that something is elaborate, with many details, without reference to the Baroque styles of the 17th and 18th centuries. The word Baroque, like most periodic or stylistic designations, was invented by later critics rather than practitioners of the arts in the 17th, the term Baroque was initially used in a derogatory sense, to underline the excesses of its emphasis. In particular, the term was used to describe its eccentric redundancy and noisy abundance of details, although it was long thought that the word as a critical term was first applied to architecture, in fact it appears earlier in reference to music. Another hypothesis says that the word comes from precursors of the style, Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola and he did not make the distinctions between Mannerism and Baroque that modern writers do, and he ignored the later phase, the academic Baroque that lasted into the 18th century. Long despised, Baroque art and architecture became fashionable between the two World Wars, and has remained in critical favour. In painting the gradual rise in popular esteem of Caravaggio has been the best barometer of modern taste, William Watson describes a late phase of Shang-dynasty Chinese ritual bronzes of the 11th century BC as baroque. The term Baroque may still be used, usually pejoratively, describing works of art, craft, the appeal of Baroque style turned consciously from the witty, intellectual qualities of 16th-century Mannerist art to a visceral appeal aimed at the senses. It employed an iconography that was direct, simple, obvious, germinal ideas of the Baroque can also be found in the work of Michelangelo. Even more generalised parallels perceived by some experts in philosophy, prose style, see the Neapolitan palace of Caserta, a Baroque palace whose construction began in 1752. In paintings Baroque gestures are broader than Mannerist gestures, less ambiguous, less arcane and mysterious, more like the stage gestures of opera, Baroque poses depend on contrapposto, the tension within the figures that move the planes of shoulders and hips in counterdirections. Baroque is a style of unity imposed upon rich, heavy detail, Baroque style featured exaggerated lighting, intense emotions, release from restraint, and even a kind of artistic sensationalism. There were highly diverse strands of Italian baroque painting, from Caravaggio to Cortona, the most prominent Spanish painter of the Baroque was Diego Velázquez. The later Baroque style gradually gave way to a more decorative Rococo, while the Baroque nature of Rembrandts art is clear, the label is less often used for Vermeer and many other Dutch artists. Flemish Baroque painting shared a part in this trend, while continuing to produce the traditional categories

4. Тосколано-Мадерно – Toscolano-Maderno is a town and comune on the West coast of Lake Garda, in the province of Brescia, in the region of Lombardy, in Italy. It is located about 40 km from Brescia, located on the Brescian shore of the Lake Garda, it includes the two towns of Toscolano, an industrial center, and Maderno, a tourist resort, united into a single comune in 1928. The municipal territory includes the Monte Pizzocolo, ghirardi, a research botanical garden Remains of a Roman villa at Toscolano, with some mosaic pavements Sanctuary of Supina

5. Италия – Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a unitary parliamentary republic in Europe. Located in the heart of the Mediterranean Sea, Italy shares open land borders with France, Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, San Marino, Italy covers an area of 301,338 km2 and has a largely temperate seasonal climate and Mediterranean climate. Due to its shape, it is referred to in Italy as lo Stivale. With 61 million inhabitants, it is the fourth most populous EU member state, the Italic tribe known as the Latins formed the Roman Kingdom, which eventually became a republic that conquered and assimilated other nearby civilisations. The legacy of the Roman Empire is widespread and can be observed in the distribution of civilian law, republican governments, Christianity. The Renaissance began in Italy and spread to the rest of Europe, bringing a renewed interest in humanism, science, exploration, Italian culture flourished at this time, producing famous scholars, artists and polymaths such as Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Michelangelo and Machiavelli. The weakened sovereigns soon fell victim to conquest by European powers such as France, Spain and Austria. Despite being one of the victors in World War I, Italy entered a period of economic crisis and social turmoil. The subsequent participation in World War II on the Axis side ended in defeat, economic destruction. Today, Italy has the third largest economy in the Eurozone and it has a very high level of human development and is ranked sixth in the world for life expectancy. The country plays a prominent role in regional and global economic, military, cultural and diplomatic affairs, as a reflection of its cultural wealth, Italy is home to 51 World Heritage Sites, the most in the world, and is the fifth most visited country. The assumptions on the etymology of the name Italia are very numerous, according to one of the more common explanations, the term Italia, from Latin, Italia, was borrowed through Greek from the Oscan Víteliú, meaning land of young cattle. The bull was a symbol of the southern Italic tribes and was often depicted goring the Roman wolf as a defiant symbol of free Italy during the Social War. Greek historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus states this account together with the legend that Italy was named after Italus, mentioned also by Aristotle and Thucydides. The name Italia originally applied only to a part of what is now Southern Italy – according to Antiochus of Syracuse, but by his time Oenotria and Italy had become synonymous, and the name also applied to most of Lucania as well. The Greeks gradually came to apply the name Italia to a larger region, excavations throughout Italy revealed a Neanderthal presence dating back to the Palaeolithic period, some 200,000 years ago, modern Humans arrived about 40,000 years ago. Other ancient Italian peoples of undetermined language families but of possible origins include the Rhaetian people and Cammuni. Also the Phoenicians established colonies on the coasts of Sardinia and Sicily, the Roman legacy has deeply influenced the Western civilisation, shaping most of the modern world

6. XVII век – The 17th century was the century that lasted from January 1,1601, to December 31,1700, in the Gregorian calendar. The greatest military conflicts were the Thirty Years War, the Great Turkish War, in the Islamic world, the Ottoman, Safavid Persian and Mughal empires grew in strength. In Japan, Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Edo period at the beginning of the century, European politics were dominated by the Kingdom of France of Louis XIV, where royal power was solidified domestically in the civil war of the Fronde. With domestic peace assured, Louis XIV caused the borders of France to be expanded and it was during this century that English monarch became a symbolic figurehead and Parliament was the dominant force in government – a contrast to most of Europe, in particular France. It was also a period of development of culture in general,1600, On February 17 Giordano Bruno is burned at the stake by the Inquisition. 1600, Michael the Brave unifies the three Romanian countries, Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania after the Battle of Șelimbăr from 1599. 1601, Battle of Kinsale, England defeats Irish and Spanish forces at the town of Kinsale, driving the Gaelic aristocracy out of Ireland and destroying the Gaelic clan system. 1601, Michael the Brave, voivode of Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania, is assassinated by the order of the Habsburg general Giorgio Basta at Câmpia Turzii, 1601–1603, The Russian famine of 1601–1603 kills perhaps one-third of Russia. 1601, Panembahan Senopati, first king of Mataram, dies and passes rule to his son Panembahan Seda ing Krapyak 1601,1602, Matteo Ricci produces the Map of the Myriad Countries of the World, a world map that will be used throughout East Asia for centuries. 1602, The Portuguese send an expeditionary force from Malacca which succeeded in reimposing a degree of Portuguese control. 1602, The Dutch East India Company is established by merging competing Dutch trading companies and its success contributes to the Dutch Golden Age. 1602, Two emissaries from the Aceh Sultanate visit the Dutch Republic,1603, Elizabeth I of England dies and is succeeded by her cousin King James VI of Scotland, uniting the crowns of Scotland and England. 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu takes the title of Shogun, establishing the Tokugawa Shogunate and this begins the Edo period, which will last until 1869. 1603–1623, After modernizing his army, Abbas I expands the Persian Empire by capturing territory from the Ottomans,1603, First permanent Dutch trading post is established in Banten, West Java. First successful VOC privateering raid on a Portuguese ship,1604, A second English East India Company voyage commanded by Sir Henry Middleton reaches Ternate, Tidore, Ambon and Banda. 1605, Gunpowder Plot failed in England,1605, The fortresses of Veszprém and Visegrad are retaken by the Ottomans. 1605, February, The VOC in alliance with Hitu prepare to attack a Portuguese fort in Ambon,1605, Panembahan Seda ing Krapyak of Mataram establishes control over Demak, former center of the Demak Sultanate. 1606, Treaty of Vienna ends anti-Habsburg uprising in Royal Hungary,1606, Assassination of Stephen Bocskay of Transylvania

7. XVIII век – The 18th century lasted from January 1,1701 to December 31,1800 in the Gregorian calendar. During the 18th century, the Enlightenment culminated in the French, philosophy and science increased in prominence. Philosophers dreamed of a brighter age and this dream turned into a reality with the French Revolution of 1789-, though later compromised by the excesses of the Reign of Terror under Maximilien Robespierre. At first, many monarchies of Europe embraced Enlightenment ideals, but with the French Revolution they feared losing their power, the Ottoman Empire experienced an unprecedented period of peace and economic expansion, taking part in no European wars from 1740 to 1768. The 18th century also marked the end of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as an independent state, the once-powerful and vast kingdom, which had once conquered Moscow and defeated great Ottoman armies, collapsed under numerous invasions. European colonization of the Americas and other parts of the world intensified and associated mass migrations of people grew in size as the Age of Sail continued. Great Britain became a major power worldwide with the defeat of France in North America in the 1760s, however, Britain lost many of its North American colonies after the American Revolution, which resulted in the formation of the newly independent United States of America. The Industrial Revolution started in Britain in the 1770s with the production of the steam engine. Despite its modest beginnings in the 18th century, steam-powered machinery would radically change human society, western historians have occasionally defined the 18th century otherwise for the purposes of their work. To historians who expand the century to include larger historical movements, 1700-1721, Great Northern War between Tsarist Russia and the Swedish Empire. 1701, Kingdom of Prussia declared under King Frederick I,1701, Ashanti Empire is formed under Osei Kofi Tutu I. 1701–1714, The War of the Spanish Succession is fought, involving most of continental Europe, 1701–1702, The Daily Courant and The Norwich Post become the first daily newspapers in England. 1702, Forty-seven Ronin attack Kira Yoshinaka and then commit seppuku in Japan,1703, Saint Petersburg is founded by Peter the Great, it is the Russian capital until 1918. 1703–1711, The Rákóczi Uprising against the Habsburg Monarchy,1704, End of Japans Genroku period. 1704, First Javanese War of Succession,1705, George Frideric Handels first opera, Almira, premieres. 1706, War of the Spanish Succession, French troops defeated at the Battles of Ramilies,1706, The first English-language edition of the Arabian Nights is published. 1707, The Act of Union is passed, merging the Scottish and English Parliaments,1707, After Aurangzebs death, the Mughal Empire enters a long decline and the Maratha Empire slowly replaces it. 1707, Mount Fuji erupts in Japan for the first time since 1700,1707, War of 27 Years between the Marathas and Mughals ends in India

8. Рококо – Rococo artists and architects used a more jocular, florid, and graceful approach to the Baroque. Their style was ornate and used light colours, asymmetrical designs, curves, unlike the political Baroque, the Rococo had playful and witty themes. By the end of the 18th century, Rococo was largely replaced by the Neoclassic style. In 1835 the Dictionary of the French Academy stated that the word Rococo usually covers the kind of ornament, style and design associated with Louis XVs reign and it includes therefore, all types of art from around the middle of the 18th century in France. The word is seen as a combination of the French rocaille and coquilles, the term may also be a combination of the Italian word barocco and the French rocaille and may describe the refined and fanciful style that became fashionable in parts of Europe in the 18th century. The Rococo love of shell-like curves and focus on decorative arts led some critics to say that the style was frivolous or merely modish, when the term was first used in English in about 1836, it was a colloquialism meaning old-fashioned. While there is some debate about the historical significance of the style to art in general. Italian architects of the late Baroque/early Rococo were wooed to Catholic Germany, Bohemia and Austria by local princes, an exotic but in some ways more formal type of Rococo appeared in France where Louis XIVs succession brought a change in the court artists and general artistic fashion. By the end of the long reign, rich Baroque designs were giving way to lighter elements with more curves. These elements are obvious in the designs of Nicolas Pineau. During the Régence, court life moved away from Versailles and this change became well established, first in the royal palace. The delicacy and playfulness of Rococo designs is seen as perfectly in tune with the excesses of Louis XVs reign. The 1730s represented the height of Rococo development in France, the style had spread beyond architecture and furniture to painting and sculpture, exemplified by the works of Antoine Watteau and François Boucher. The Rococo style was spread by French artists and engraved publications, william Hogarth helped develop a theoretical foundation for Rococo beauty. Though not intentionally referencing the movement, he argued in his Analysis of Beauty that the lines and S-curves prominent in Rococo were the basis for grace. The development of Rococo in Great Britain is considered to have connected with the revival of interest in Gothic architecture early in the 18th century. The beginning of the end for Rococo came in the early 1760s as figures like Voltaire and Jacques-François Blondel began to voice their criticism of the superficiality, Blondel decried the ridiculous jumble of shells, dragons, reeds, palm-trees and plants in contemporary interiors. By 1785, Rococo had passed out of fashion in France, replaced by the order, in Germany, late 18th century Rococo was ridiculed as Zopf und Perücke, and this phase is sometimes referred to as Zopfstil

9. Маньеризм – Mannerism is a style in European art that emerged in the later years of the Italian High Renaissance around 1520, lasting until about 1580 in Italy, when the Baroque style began to replace it. Northern Mannerism continued into the early 17th century, stylistically, Mannerism encompasses a variety of approaches influenced by, and reacting to, the harmonious ideals associated with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and early Michelangelo. Where High Renaissance art emphasizes proportion, balance, and ideal beauty, Mannerism exaggerates such qualities, Mannerism is notable for its intellectual sophistication as well as its artificial qualities. Mannerism favors compositional tension and instability rather than the balance and clarity of earlier Renaissance painting, Mannerism in literature and music is notable for its highly florid style and intellectual sophistication. The definition of Mannerism and the phases within it continue to be a subject of debate among art historians, for example, some scholars have applied the label to certain early modern forms of literature and music of the 16th and 17th centuries. The term is used to refer to some late Gothic painters working in northern Europe from about 1500 to 1530. Mannerism also has been applied by analogy to the Silver Age of Latin literature, the word mannerism derives from the Italian maniera, meaning style or manner. Like the English word style, maniera can either indicate a type of style or indicate an absolute that needs no qualification. Vasari was also a Mannerist artist, and he described the period in which he worked as la maniera moderna, james V. Mirollo describes how bella maniera poets attempted to surpass in virtuosity the sonnets of Petrarch. This notion of bella maniera suggests that artists thus inspired looked to copying and bettering their predecessors, in essence, bella maniera utilized the best from a number of source materials, synthesizing it into something new. As a stylistic label, Mannerism is not easily defined, “High Renaissance” connoted a period distinguished by harmony, grandeur and the revival of classical antiquity. The term Mannerist was redefined in 1967 by John Shearman following the exhibition of Mannerist paintings organised by Fritz Grossmann at Manchester City Art Gallery in 1965. The label “Mannerism” was used during the 16th century to comment on social behaviour, however, for later writers, such as the 17th-century Gian Pietro Bellori, la maniera was a derogatory term for the perceived decline of art after Raphael, especially in the 1530s and 1540s. From the late 19th century on, art historians have used the term to describe art that follows Renaissance classicism. By the end of the High Renaissance, young artists experienced a crisis, no more difficulties, technical or otherwise, remained to be solved. The young artists needed to find a new goal, and they sought new approaches, at this point Mannerism started to emerge. The new style developed between 1510 and 1520 either in Florence, or in Rome, or in both cities simultaneously and this period has been described as a natural extension of the art of Andrea del Sarto, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Michelangelo from an early age had developed a style of his own, one of the qualities most admired by his contemporaries was his terribilità, a sense of awe-inspiring grandeur, and subsequent artists attempted to imitate it

10. Далмация – Dalmatia is one of the four historical regions of Croatia, alongside Croatia proper, Slavonia, and Istria. Dalmatia is a belt of the east shore of the Adriatic Sea. The hinterland ranges in width from fifty kilometres in the north, to just a few kilometres in the south,79 islands run parallel to the coast, the largest being Brač, Pag and Hvar. The largest city is Split, followed by Zadar, Dubrovnik, the name of the region stems from an Illyrian tribe called the Dalmatae, who lived in the area in classical antiquity. Later it became a Roman province, and as result a Romance culture emerged, along with the now-extinct Dalmatian language, later largely replaced with related Venetian. With the arrival of Croats to the area in the 8th century, who occupied most of the hinterland, Croatian and Romance elements began to intermix in language and the culture. During the Middle Ages, its cities were conquered by, or switched allegiance to. The longest-lasting rule was the one of the Republic of Venice, between 1815 and 1918, it was as a province of Austrian Empire known as the Kingdom of Dalmatia. It was the Romans who first gave Dalmatia its name, inspired by the Illyrian word “delmat”, meaning a proud and its Latin form Dalmatia gave rise to its current English name. In the Venetian language, once dominant in the area, it is spelled Dalmàssia, the modern Croatian spelling is Dalmacija, pronounced. Dalmatia is referenced in the New Testament at 2 Timothy 4,10 so its name has been translated in many of the worlds languages. In antiquity the Roman province of Dalmatia was much larger than the present-day Split-Dalmatia County, Dalmatia is today a historical region only, not formally instituted in Croatian law. Its exact extent is uncertain and subject to public perception. According to Lena Mirošević and Josip Faričić of the University of Zadar, simultaneously, the southern part of Lika and upper Pounje, which were not a part of Austrian Dalmatia, became a part of Zadar County. From the present-day administrative and territorial point of view, Dalmatia comprises the four Croatian littoral counties with seats in Zadar, Šibenik, Split, Dalmatia is therefore generally perceived to extend approximately to the borders of the Austrian Kingdom of Dalmatia. The Encyclopædia Britannica defines Dalmatia as extending to the narrows of Kotor, other sources, however, such as the Treccani encyclopedia and the Rough Guide to Croatia still include the Bay as being part of the region. This definition does not include the Bay of Kotor, nor the islands of Rab, Sveti Grgur and it also excludes the northern part of the island of Pag, which is part of the Lika-Senj County. However, it includes the Gračac Municipality in Zadar County, which was not a part of the Kingdom of Dalmatia and is not traditionally associated with the region, the inhabitants of Dalmatia are culturally subdivided into two or three groups

wikivisually.com

Челести, Андреа — Википедия

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

Мадонна с младенцем и святой Анной иблагословляющим святым Иаковом. Холст, масло.Епархиальный музей (Брешия) / Museo diocesano (Brescia)Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:

Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]

Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

ru.mobile.bywiki.com

Андреа Челести Википедия

Андре́а Челе́сти (итал. Andrea Celesti ; 1637, Венеция — 1712, Тосколано) — итальянский художник венецианской школы второй половины XVII — начала XVIII века. Наследник венецианских колористов, он разрабатывал традиционную для эпохи барокко канву религиозно-мифологических сюжетов. Позднее его приёмы стремительно-воздушной лёгкости красочной кладки[1] очень пригодились живописцам рококо[2].

Биография

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

Мадонна с младенцем и святой Анной иблагословляющим святым Иаковом. Холст, масло.Епархиальный музей (Брешия) / Museo diocesano (Brescia)Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:

Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]

Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

Литература

- Государственный музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина. Каталог живописи / Под общ. ред.: И. Е. Даниловой; Пер. на англ. яз.: Э. Бромфилд. — Москва, Милан: ART-MIF, Mazzotta, 1995. — С. 210—211. — 775 с.

- История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, Москва: Издательский Дом “Нева”, ОЛМА—ПРЕСС, 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с. — ISBN 5765421105.

- Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи : Италия. Испания. Франция. Швейцария / Вступ. статья В. Ф. Левинсон-Лессинга. — Москва, Ленинград: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.

- Andrea Celesti a Desenzano : capolavori nella chiesa di S. Maria Maddalena. — Acherdo Edizioni, 2009. — 69 p. — ISBN 8890415304.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : la Strage degli innocenti restaurata. — Brescia: Grafo, 2007. — 69 p. — ISBN 8873857426.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : capolavori restaurati nella Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo. — Brescia, Italy: Grafo, 2006. — 100 p.

- Isabella Marelli; Giuliana Algeri. Andrea Celesti (1637-1712) : un pittore sul Lago di Garda. — Brescia: San Felice del Benaco, 2000. — 369 p. — 2000 экз.

- Giovanni Agosti; Elena Lucchesi Ragni. Andrea Celesti nel Bresciano : per il restauro del ciclo di Toscolano (1678—1712). Exhibition catalog. — Brescia, Italy: Civici Musei d'arte e storia, 1993. — 47 p.

- Camillo Boselli Appunti bresciani ad un libro su Andrea Celesti (Italiano) // Arte veneta / Istituto di Storia dell'Arte. — Venezia. — Università di Padova, 1955. — № 33—36. — С. 234—236.

- Antonio Morassi. Il pittore Andrea Celesti. — Milano: Silvana, 1954. — P. 168.

Галерея

Ссылки

- 6 работ Андреа Челести, включая монументальные

- Моника Мольтени (Monica Molteni), профессор Университета Вероны (англ.), о современных исследованиях живописи Андреа Челести и проблемах реставрации (ВИДЕО, 4 мин.) (итал.)

- Интересно проследить за методом создания композиции на примере рисунка, исполненного тушью, «Похищение Европы» (20 x 26.7 см), атрибутируемого Андреа Челести.

- Сравним с небольшим эскизом Андреа Челести «Сцена оплакивания мёртвого Христа» (перо, тушь 14 x 9.8 см).

- Ещё один рисунок, приписываемый А. Челести из музея Метрополитен в Нью-Йорке: эскиз для заказной картины «Аллегория власти Венеции» (отмывка коричневой тушью, перо, сангина, 37.0 x 28.5 см), основательно прорисованная аллегорическая многофигурная композиция[6].

Примечания

- ↑ Русский художник и историк искусства Александр Бенуа называет живописную манеру Андреа Челести «красивой и сочной». См: История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, М., 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с.

- ↑ По словам крупного знатока итальянской живописи, Макса Геринга,

за двадцать лет до рождения Гварди, Андреа Челести достиг импрессионистского растворения формы

— (См: Max Goering. Francesco Guardi. — First Edition. — Wien: Anton Schroll & Co., 1944. — P. 30. — 86 p. — ISBN 0011251239.) - ↑ Андреа Челести 1637—1706. Венецианская школа. Учился у Маттео Панцоне, испытал влияние венецианских художников XVI в. Работал в Венеции. Писал картины на религиозные и мифологические темы и портреты. (В книге: Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи. — М., Л.: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.)

- ↑ Ivanoff N. Celesti, Andrea // Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. — Rome: Institutto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

- ↑ Программа фестиваля «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести» Borghese, Fabio. Andrea Celesti, il teatro del colore. «Treccani» La cultura italiana (20 февраля 2014). Проверено 22 января 2016. (итал.)

- ↑ Рисунок «Аллегория власти Венеции» опубликован в капитальном томе: Jacob Bean, Lawrence Turčić. 17th century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. — New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979. — P. 94—95.

wikiredia.ru

Художник Челести Википедия

Андре́а Челе́сти (итал. Andrea Celesti ; 1637, Венеция — 1712, Тосколано) — итальянский художник венецианской школы второй половины XVII — начала XVIII века. Наследник венецианских колористов, он разрабатывал традиционную для эпохи барокко канву религиозно-мифологических сюжетов. Позднее его приёмы стремительно-воздушной лёгкости красочной кладки[1] очень пригодились живописцам рококо[2].

Биография

Андреа Челести родился в 1637 году в Венеции. Сын художника англ. Стефано Челести (известны работы после 1635, ум. после 1659), Андреа брал первые уроки живописи у своего отца. Затем он обучался в мастерской венецианского маньериста англ. Маттео Панцоне (Zanetti)[3] (ок. 1586 — после 1663; художника родом из Далмации, некогда учившегося у Джакомо Пальмы младшего). Позднее, Андреа продолжил обучение у англ. Себастьяно Маццони (Temanza), ок. 1611—1678.

В Венеции Андреа Челести быстро развился в преуспевающего, обласканного художника. Он так хорошо исполнял большие заказы, что дож Альвизе Контарини удостоил его звания кавалера[4] в 1681 году.

На первых шагах в его живописи заметно увлечение караваджистским натурализмом, эффектами англ. tenebroso. Но постепенно, в том числе под воздействием другого удачливого венецианского живописца, прославившегося стремительным темпом работы, Луки Джордано, краски в его полотнах обретают бо́льшую звучность за счёт просвечивающего сквозь прозрачный слой красноватого светлого грунта.

Мадонна с младенцем и святой Анной иблагословляющим святым Иаковом. Холст, масло.Епархиальный музей (Брешия) / Museo diocesano (Brescia)Приближённость к высшей власти в Венецианской республике обеспечивала постоянную занятость и самому художнику, и его боттеге, но со смертью покровительствовавшего ему дожа, Андреа Челести покидает Венецию (говорили даже о его изгнании, что не было бы удивительно, если подумать, скольких врагов он нажил в годы процветания). В 1688 году художник поселяется в Тосколано, на берегу озера Гарда в Ломбардии. Здесь Андреа Челести активно работает над большими росписями в местных церквах и виллах. Около 1700 года Челести вернулся в Венецию, где он вновь создал мастерскую.

Праздничная, вдохновенная интонация его красок подчёркивается сказочной декоративностью общей атмосферы, ассоциирующейся с театральной постановкой.

В Италии чтут память о художнике. В Тосколано, в окрестностях Брешии, где Андреа Челести жил и работал много лет и где сохранилось много его росписей, проводятся фестивали культуры его имени. В феврале-марте 2014 такой фестиваль назывался «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести»:

Nei nome di Andrea Celesti, mago del colore veneziano che strego il lago di Garda, un progetto culture promosso dai commune di Toscolano Maderno per riscoprire sentieri di arte e bellezza dai Settecento ad oggi.

[5]

Живопись Андреа Челести определённо влияла на начальный период развитие стиля рококо, в первые годы XVIII века. Отголоски приподнято-мажорного, мерцающего колорита работ Челести можно отыскать (понятно, со скидкой на различие эпох и культур) у Антуана Ватто и даже у Оноре Фрагонара.

Литература

- Государственный музей изобразительных искусств имени А. С. Пушкина. Каталог живописи / Под общ. ред.: И. Е. Даниловой; Пер. на англ. яз.: Э. Бромфилд. — Москва, Милан: ART-MIF, Mazzotta, 1995. — С. 210—211. — 775 с.

- История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, Москва: Издательский Дом “Нева”, ОЛМА—ПРЕСС, 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с. — ISBN 5765421105.

- Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи : Италия. Испания. Франция. Швейцария / Вступ. статья В. Ф. Левинсон-Лессинга. — Москва, Ленинград: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.

- Andrea Celesti a Desenzano : capolavori nella chiesa di S. Maria Maddalena. — Acherdo Edizioni, 2009. — 69 p. — ISBN 8890415304.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : la Strage degli innocenti restaurata. — Brescia: Grafo, 2007. — 69 p. — ISBN 8873857426.

- Andrea Celesti a Toscolano : capolavori restaurati nella Chiesa dei Santi Pietro e Paolo. — Brescia, Italy: Grafo, 2006. — 100 p.

- Isabella Marelli; Giuliana Algeri. Andrea Celesti (1637-1712) : un pittore sul Lago di Garda. — Brescia: San Felice del Benaco, 2000. — 369 p. — 2000 экз.

- Giovanni Agosti; Elena Lucchesi Ragni. Andrea Celesti nel Bresciano : per il restauro del ciclo di Toscolano (1678—1712). Exhibition catalog. — Brescia, Italy: Civici Musei d'arte e storia, 1993. — 47 p.

- Camillo Boselli Appunti bresciani ad un libro su Andrea Celesti (Italiano) // Arte veneta / Istituto di Storia dell'Arte. — Venezia. — Università di Padova, 1955. — № 33—36. — С. 234—236.

- Antonio Morassi. Il pittore Andrea Celesti. — Milano: Silvana, 1954. — P. 168.

Галерея

Ссылки

- 6 работ Андреа Челести, включая монументальные

- Моника Мольтени (Monica Molteni), профессор Университета Вероны (англ.), о современных исследованиях живописи Андреа Челести и проблемах реставрации (ВИДЕО, 4 мин.) (итал.)

- Интересно проследить за методом создания композиции на примере рисунка, исполненного тушью, «Похищение Европы» (20 x 26.7 см), атрибутируемого Андреа Челести.

- Сравним с небольшим эскизом Андреа Челести «Сцена оплакивания мёртвого Христа» (перо, тушь 14 x 9.8 см).

- Ещё один рисунок, приписываемый А. Челести из музея Метрополитен в Нью-Йорке: эскиз для заказной картины «Аллегория власти Венеции» (отмывка коричневой тушью, перо, сангина, 37.0 x 28.5 см), основательно прорисованная аллегорическая многофигурная композиция[6].

Примечания

- ↑ Русский художник и историк искусства Александр Бенуа называет живописную манеру Андреа Челести «красивой и сочной». См: История живописи всех времен и народов. — СПб, М., 2002. — Т. 3. — С. 304. — 512 с.

- ↑ По словам крупного знатока итальянской живописи, Макса Геринга,

за двадцать лет до рождения Гварди, Андреа Челести достиг импрессионистского растворения формы

— (См: Max Goering. Francesco Guardi. — First Edition. — Wien: Anton Schroll & Co., 1944. — P. 30. — 86 p. — ISBN 0011251239.) - ↑ Андреа Челести 1637—1706. Венецианская школа. Учился у Маттео Панцоне, испытал влияние венецианских художников XVI в. Работал в Венеции. Писал картины на религиозные и мифологические темы и портреты. (В книге: Эрмитаж (Ленинград). Отдел западноевропейского искусства : Каталог живописи. — М., Л.: Искусство, 1958. — Т. 1. — С. 208. — 479 с.)

- ↑ Ivanoff N. Celesti, Andrea // Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. — Rome: Institutto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1979.

- ↑ Программа фестиваля «Театр цве́та Андреа Челести» Borghese, Fabio. Andrea Celesti, il teatro del colore. «Treccani» La cultura italiana (20 февраля 2014). Проверено 22 января 2016. (итал.)

- ↑ Рисунок «Аллегория власти Венеции» опубликован в капитальном томе: Jacob Bean, Lawrence Turčić. 17th century Italian Drawings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. — New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979. — P. 94—95.

wikiredia.ru